In 1498, just one year after Italian explorer Giovanni Caboto rediscovered North America and six years after fellow Italian Christopher Columbus “discovered” the New World, Portuguese explorers João Fernandes Lavrador and Pêro de Barcelos were the first modern explorers of much of northeastern North America, including the Labrador Peninsula. They were followed (1500-02) by Portuguese explorers Gaspar and Miguel Corte Real. This is the story of Portuguese exploration of North America, the fourth in the IAT Natural and Cultural Heritage Series.

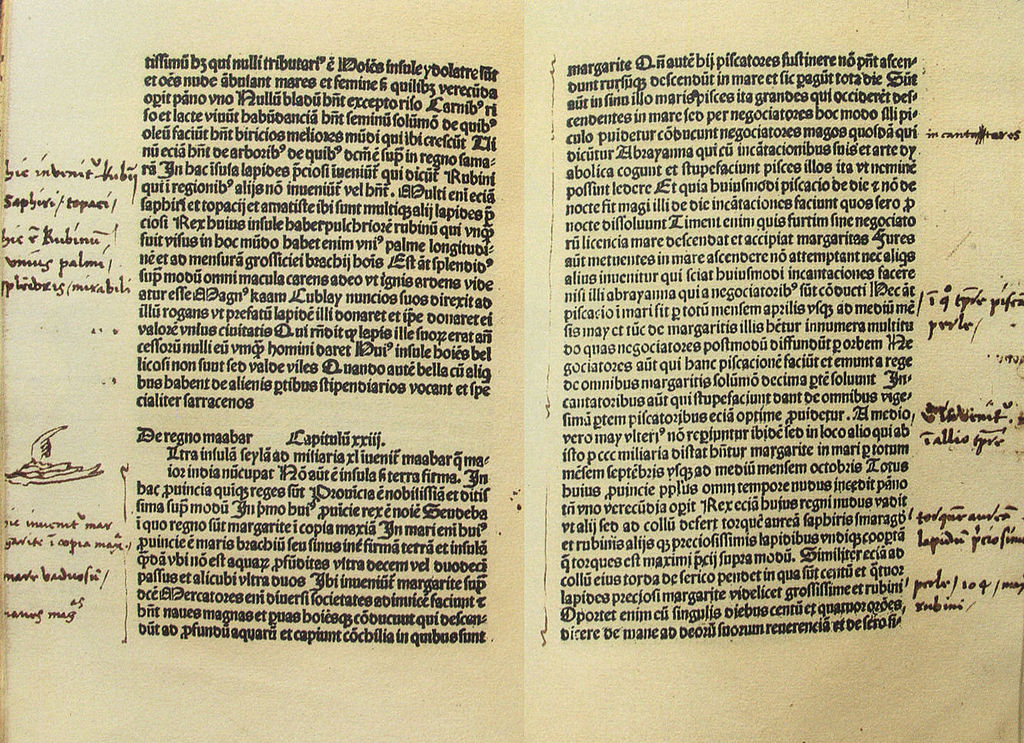

In 1295, when Italian merchant Marco Polo returned to his native Venice after 24 years travelling across Asia to China with his father Niccolò and uncle Maffeo, few Europeans had any knowledge of lands beyond the Near East, where four years earlier, 200 years of Christian military campaigns to the Holy Land known as the Crusades had ended.

However the Polos returned at a time when Venice was at war with Genoa, another wealthy Italian city-state with an extensive Mediterranean trading network. After outfitting a galley for war, he was soon captured and imprisoned for approximately 3 years, during which time he dictated a detailed account of his travels to fellow prisoner Rustichello da Pisa, who after adding his and other tales, published a book with the English title The Travels of Marco Polo.

Though written before the invention of Gutenberg’s printing press (c. 1439), the book was widely copied in many languages, inspiring merchants, seamen and nobility with tales of riches in the far east. Already experienced traders in the eastern Mediterranean, Italian city-states were well positioned to capitalize on increased trade with Arab and Turkish middlemen.

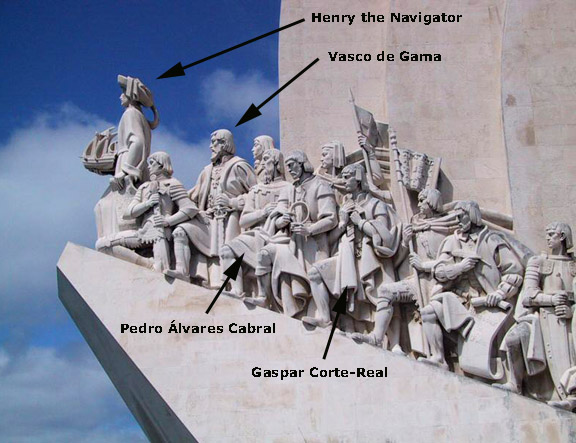

However in the early 15th century, another bold and visionary European had another idea. He would pursue trade directly with the far east, avoiding non-Christian middlemen. Portugal’s Infante Dom Henrique de Avis, Duke of Viseu, better known in the 20th century as Henry the Navigator (1394-1460), would devise a plan to reach Asia by sailing around Africa, from the Atlantic to Indian Ocean.

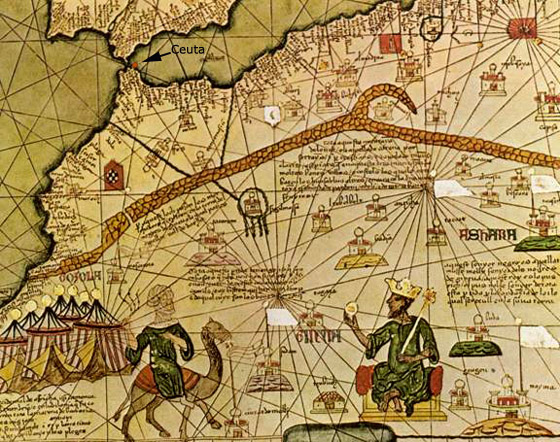

In 1415 at the age of 21, Henry convinced his father, King John I, to conquer the port of Ceuta on the North African coast. This Moorish stronghold in the Strait of Gibraltar had long been used as a base for Barbary pirates who raided the Portuguese coast, capturing locals and selling them in the African slave market. Soon after, he was exploring the West African coast, hunting pirates and seeking the source of the area’s lucrative gold trade and the legendary Christian Kingdom of Prester John.

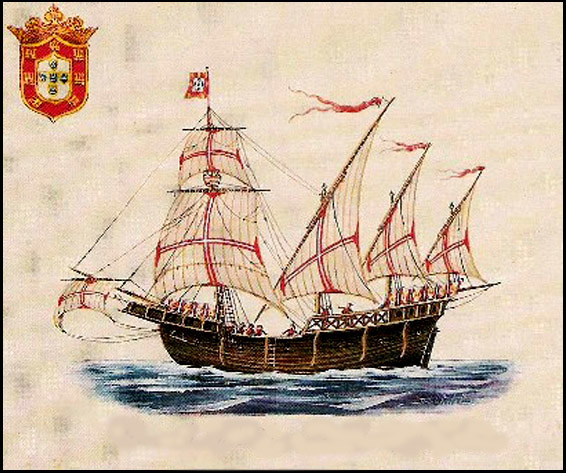

Because Mediterranean ships of the era were too slow and heavy for these dangerous forays into the Atlantic Ocean, a new and much lighter ship was developed that was faster and more maneuverable. Rigged with 2 or 3 lateen sails, these shallow-keeled Portuguese caravels of 50 to 150 tons were able to tack against the wind and sail upriver into shallow coastal waters.

Soon Henry’s explorers were discovering new lands in the eastern Atlantic, including the Madeira Islands (1420) and Azores (1430), which were quickly colonized. They also discovered the volta do mar (Portuguese for “turn of the sea“), the navigational technique whereby mariners returning to Portugal from the west coast of Africa had to follow the clockwise currents and trade winds and sail northwest to reach northeast. This was a major innovation in Atlantic navigation that would play a major role in future exploration. By the time of Henry’s death in 1460, Portuguese caravels had discovered the Cape Verde Archipelago and circumvented the Muslin land-based trade routes across the western Sahara Desert, thus enabling direct trade for gold and slaves.

During the generation that followed, Portuguese explorers continued south along the west coast of Africa until 1488 when Bartolomeu Dias sailed around the southernmost tip of the continent, becoming the first European to reach the Indian Ocean from the Atlantic. Four years later in 1492, Christopher Columbus followed the volta do mar on his first voyage west across the Atlantic Ocean in search of the East Indies.

On October 12 he landed on a Bahamian Island which he claimed for supporting monarchs Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile, after being rejected by King John II of Portugal on the basis that his estimated travel distance of 2400 miles was far too low and Diaz had already rounded the “Cape of Good Hope” for an eastern maritime route to Asia.

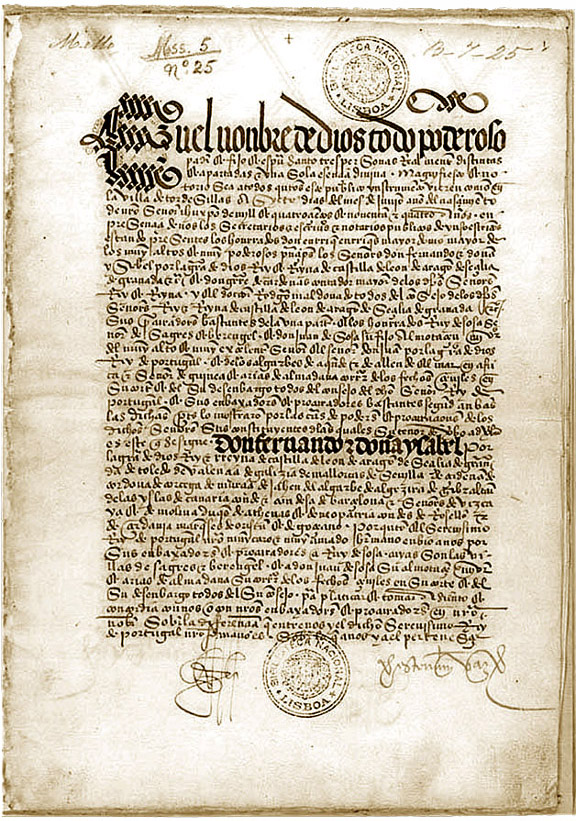

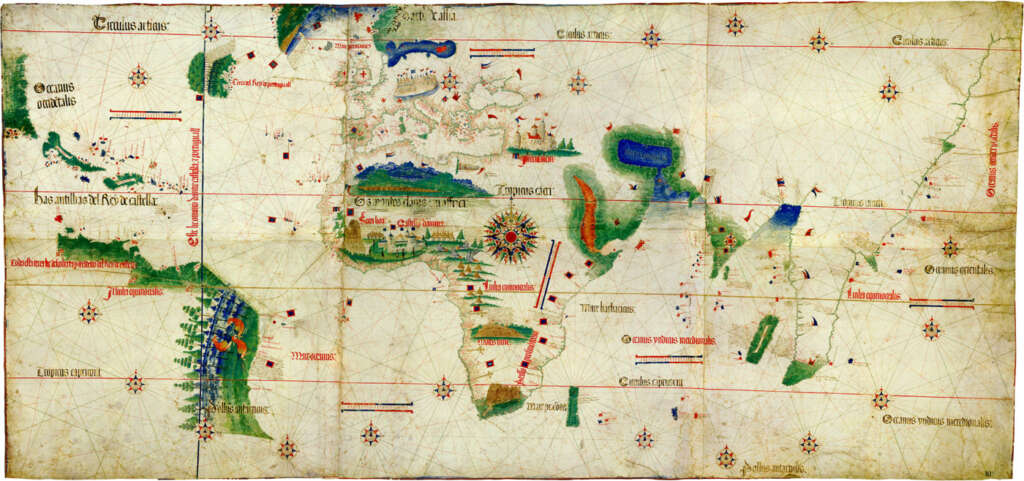

This new discovery precipitated a dispute between Spain and Portugal, which had been granted all lands south of the Canary Islands in the Alcaçovas Treaty of 1479, which ended the War of the Castilian Succession (1475-1479). The dispute was resolved by the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494, which divided all new lands in the Atlantic Ocean between the Portuguese and Spanish empires along a meridian 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde Islands, approximately halfway between those islands and the islands discovered by Columbus in 1492. Lands to the west of the meridian would belong to Spain, while lands to the east would belong to Portugal.

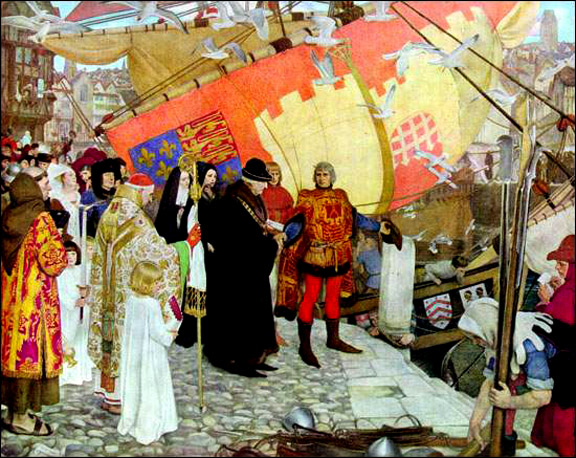

In just three years, Venetian Giovanni Caboto became the first European to reach Newfoundland in North America since the Norse Greenlanders, approximately 500 years earlier. Sailing with a royal patent from England to find a northwest route to the East Indies, his discovery would complicate future Portuguese and Spanish claims to the New World.

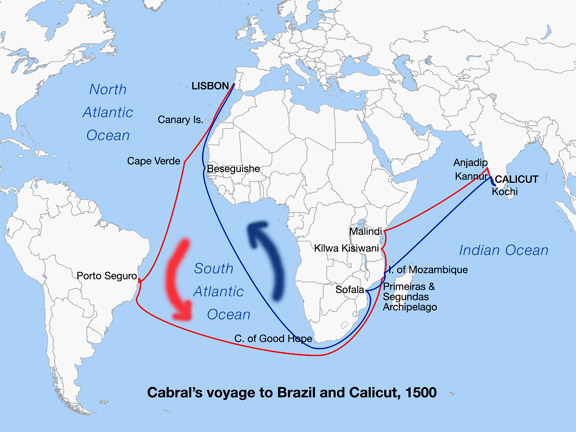

That same year, Vasco da Gama departed Portugal for India, following Diaz’s route south into the Indian Ocean, where in 1498 he became the first European to reach India by sea. Two years later, countryman Pedro Álvares Cabral followed the counter clockwise ocean currents and trade winds of the South Atlantic on his voyage to India, and in the process discovered the northeast coast of South America, claiming the future “Brazil” for Portugal.

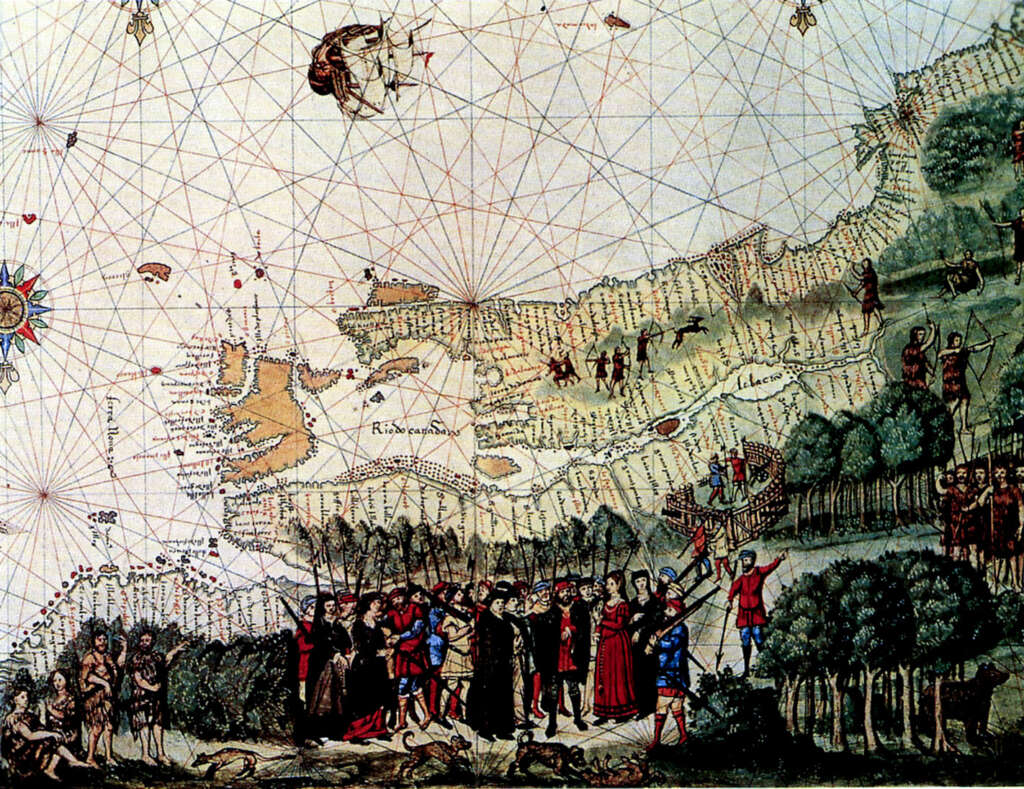

While Cabral was exploring the southwest Atlantic, Portuguese explorer Gaspar Corte-Real and his brother Miguel were exploring the northwest and reached what is believed to be Newfoundland. Though Miguel returned to Portugal with two of the expedition’s three ships, Gaspar continued southwards and was never heard from again. Miguel met the same fate the following year, when he set off in search of his younger brother. As a result of these voyages the names Terra Cortereal and Terra del Rey de Portuguall began to appear on European maps of the day.

The Corte Reals were following in the wake of fellow Azores countryman João Fernandes Lavrador, who in 1498 was granted a patent by Portuguese King Manuel I to search for new lands on the Portuguese side of the Tordesillas Meridian. He reached Greenland and Labrador, named Island of Labrador and Land of Labrador, respectively, and was granted title to many of the lands he discovered. In 1501, he too was lost at sea in the North Atlantic.

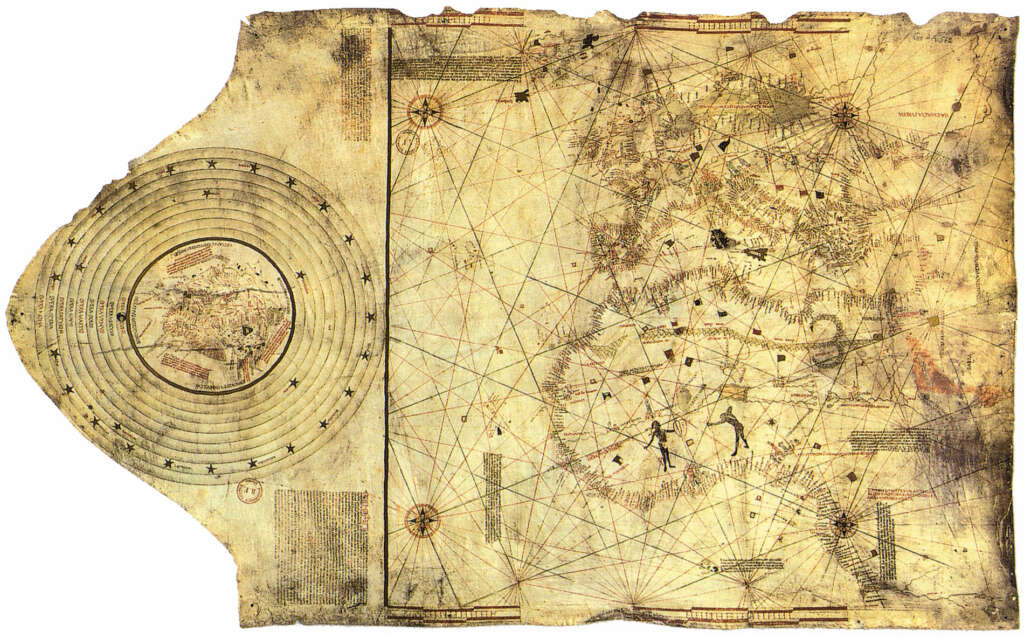

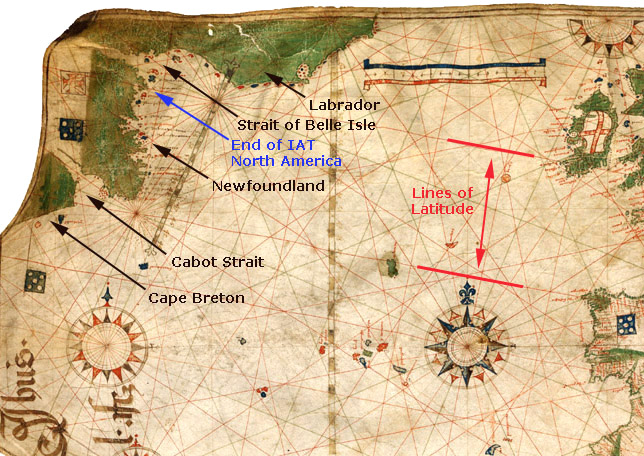

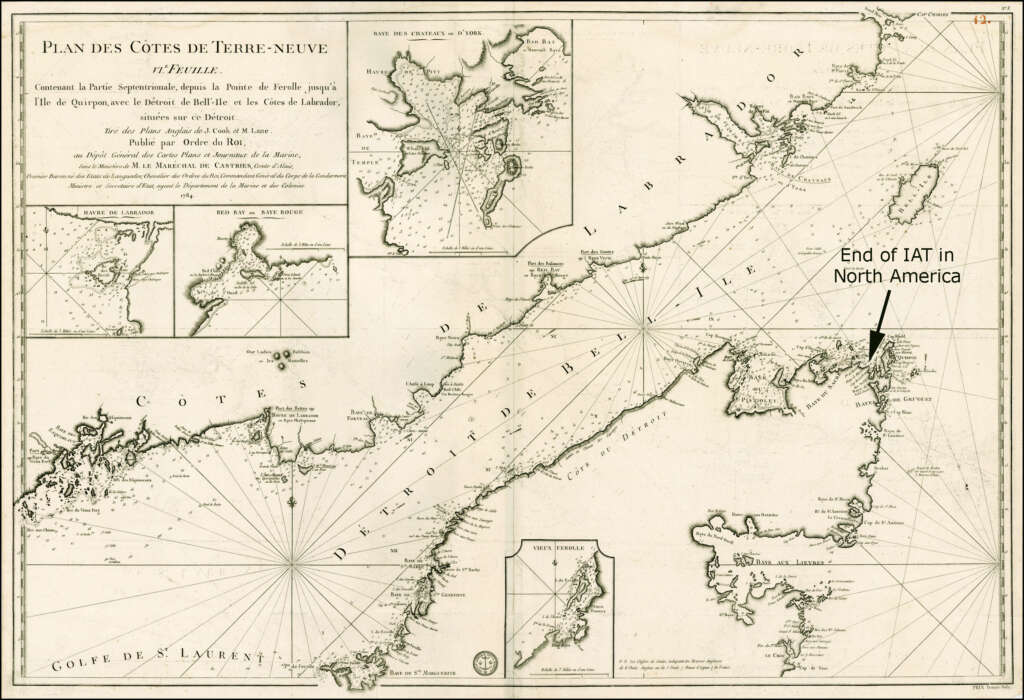

The Portuguese Pedro Reinel Map of 1504, the world’s first to include lines of latitude, clearly shows the Canadian regions of Labrador, Newfoundland and Cape Breton, as well as the Strait of Belle Isle and Cabot Strait.

500 years earlier, the coast of Labrador and Strait of Belle Isle were familiar to Norse explorers from Greenland, beginning with Leif Erikson who established the settlement of Vinland at the tip of Newfoundland’s Great Northern Peninsula.

In 1534 and 1535, Jacques Cartier entered the Gulf of St. Lawrence via the Strait of Belle Isle during his first two voyages of discovery. In 1536 after overwintering in “Canada”, he returned to France via the Cabot Strait, thus becoming the first European on record to determine Newfoundland to be one or more islands.

Though the first French explorer of “Canada”, Cartier was not the first explorer flying the French flag in North America. in 1524, Florentine Giovanni da Verrazzano explored the east coast from North Carolina to Newfoundland in the service of King Francis I.

For the next half century, the Strait of Belle Isle continued to establish itself as Canada’s Heritage Gateway, when whaling fleets from the Basque region of France and Spain (whose King Phillip II was also crowned Philip I of Portugal in 1581) hunted right and bowhead whales as they migrated through the strait between the Gulf of St. Lawrence and Labrador Sea.

In spite of the Portuguese claim to North America under the Treaty of Tordesillas and the voyages of João Fernandes Lavrador and Gaspar Corte-Real, Giovanni Caboto’s discovery of Newfoundland on behalf of King Henry VII of England one year before Lavrador’s voyage in 1498 established “British title to the territory composing [Canada and] the United States. That title was founded on the right of discovery, a right which was held among the European nations a just and sufficient foundation, on which to rest their respective claims to the American continent. Whatever controversies existed among them (and they were numerous), respecting the extent of their own acquisitions abroad, they appealed to this as the ultimate fact, by which their various and conflicting claims were to be adjusted.” (Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States, by Joseph Story, LL. D, U.S. Supreme Court Justice, and Dane Professor of Law, Harvard University, 1833).

The English claim to North America was disputed by its historic rival France, based on the voyages of Jacques Cartier who discovered the St. Lawrence River and the interior of “Canada”. After the English victory in the Seven Years War (French and Indian War in North America, 1754-1763), England finally gained possession of the continent and quickly employed James Cook to survey and chart the Strait of Belle Isle and French Shore of Newfoundland, which together with the islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon, were the only remaining territories under limited French control.

The victory was short lived. Twenty years later, England lost the southern half to the American States during the Revolutionary War for independence.

As for Portugal, they continue to fish in Newfoundland waters, an enduring tradition lasting over 500 years. In Labrador, one of the biggest employers today is the mining company Vale, a Portuguese language multinational based in the Tordesillas Meridiancountry of Brazil.

And in Portugal, the country proudly remembers their classic age of exploration, a time when their country was without equal on the high seas.