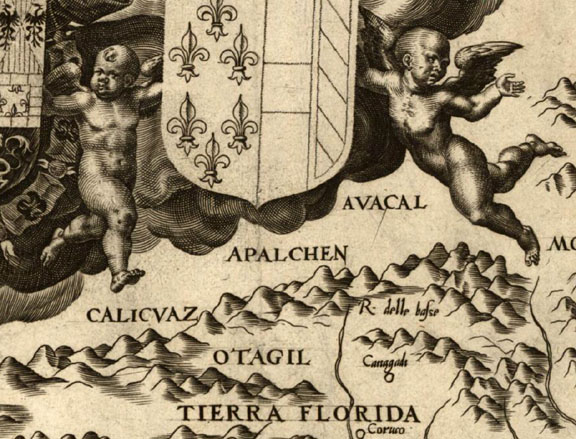

As the name suggests, the International Appalachian Trail winds its way across sections of North America’s Appalachian Mountains, before crossing the Atlantic Ocean and following other Pangea related mountains of Western Europe and North Africa. Though the mountains themselves were formed over 250 million years ago when continental plates collided, what is the origin of the name “Appalachian”, the fourth oldest surviving European place name in the United States?

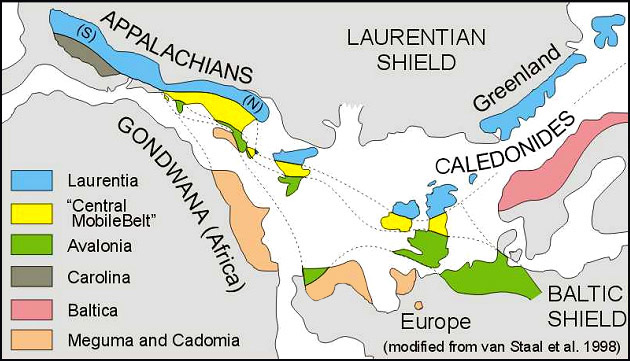

Our story begins with Christopher Columbus (c.1450-1506), an Italian merchant and navigator from Genoa who sought financial support for a westward voyage across the Atlantic Ocean in search of the East Indies.

Columbus was inspired by The Travels of Marco Polo and the ideas of Florentine astronomer Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli who theorized that sailing west across the Atlantic Ocean would be a more expedient way to reach the riches of the east.

After twice being rejected by King John II of Portugal (who, after the successful voyage of Bartholomew Diaz around the Cape of Good Hope in 1488, already had a sea route east), Columbus succeeded in receiving support from Spanish Monarchs Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon.

On August 3, 1492, Columbus set sail from Palos de la Frontera, Spain on his first of four voyages west across the Atlantic Ocean.

After resupplying at Castille’s Canary Islands off the west coast of Africa, he departed September 6 on what would be a 5-week voyage to the Bahama Islands, first sighting land on October 12.

Within 10 years and after 3 more voyages, Columbus had explored most of the Caribbean and the east coast of Central America, where he was told by natives of another ocean to the west.

It was Spanish explorer and conquistador Vasco Núñez de Balboa (c.1475-1519), who in 1513, crossed the Isthmus of Panama and became the first European to reach the Pacific Ocean from the New World.

Fellow conquistador Juan Ponce de León (1474-1521) joined Columbus on his second voyage in 1493, and after serving as the first governor of Puerto Rico (1509-1511), set out on March 4, 1513 to search for new lands rumored to be to the north. On April 2 during the Easter Season (which the Spaniards called Pascua Florida – Festival of Flowers), he sighted a verdant landscape on the east coast of Florida, which he named La Florida.

Fifteen years later, in April, 1528, Conquistador Pánfilo de Narváez and a fleet of 5 ships arrived on the west coast of Florida near what is now Tampa Bay. With 300 men, he landed and marched north through the interior in search of gold and other riches, until they reached a Native American village near present-day Tallahassee, whose name they transcribed as Apalchen or Apalachen.

Encountering hostility from the natives, they retreated to the coast where Narváez was swept out to see on a raft and never seen again. After eight years and many ordeals, only 4 survivors lived to reach Spanish forces in Mexico. In the years that followed, the names Apalchen and Apalachee were used to describe the Florida tribe and interior region to the north.

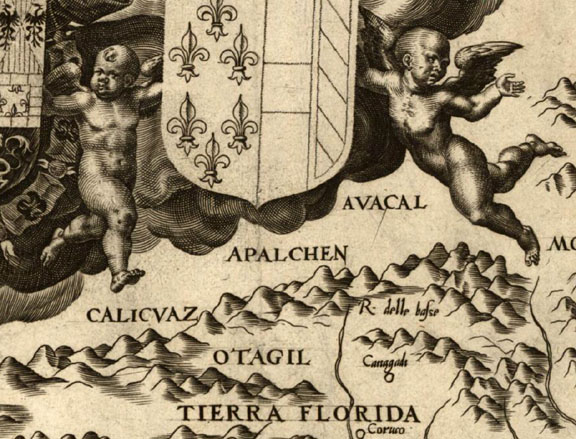

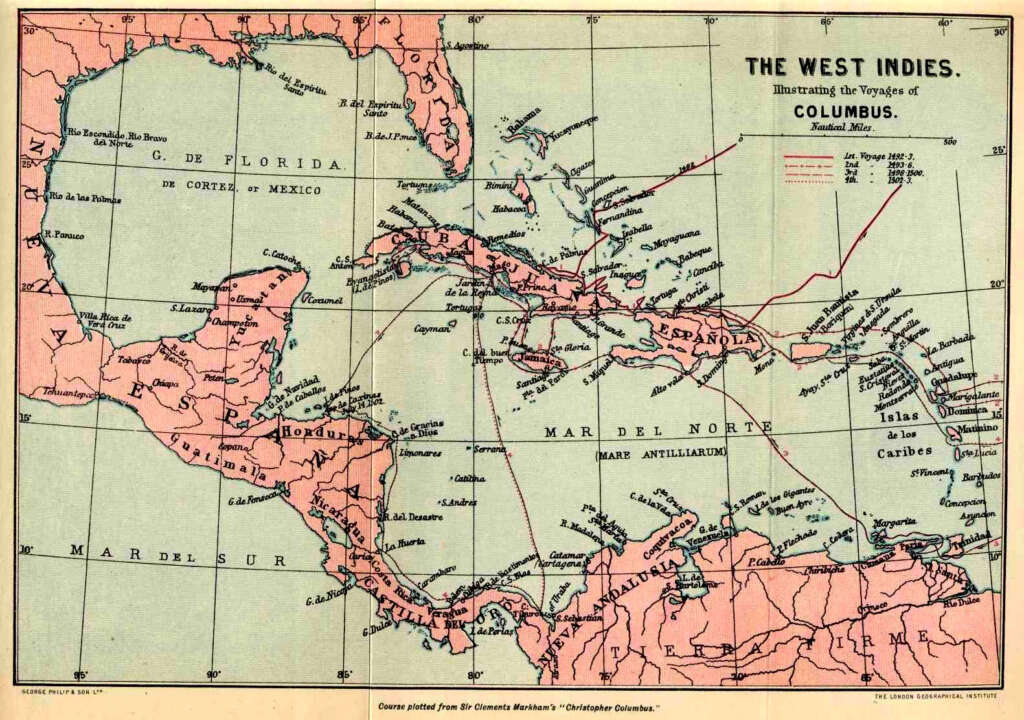

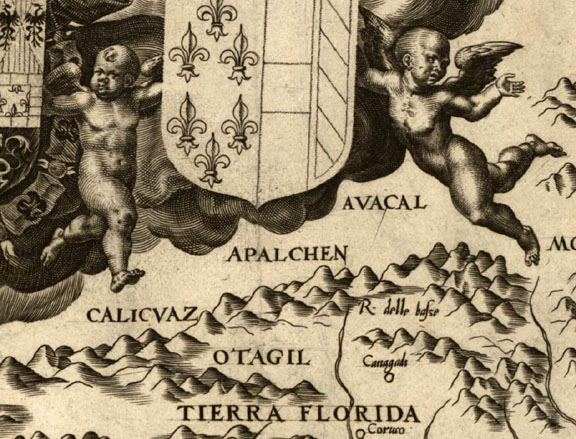

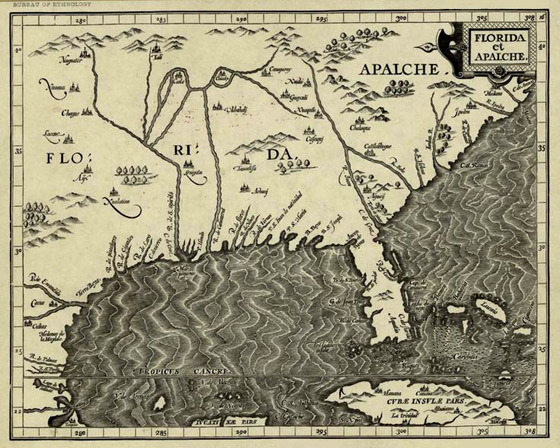

The Diego Gutiérrez map of the New World (above and below) entitled Americae Sive Quartae Orbis Partis Nova Et Exactissima Descriptio was printed in 1562 and was the first to record the names “Apalchen” (or a derivative) and “California”. It was printed in Antwerp for the Casa de Contratación, the Spanish government agency which attempted to control all Spanish exploration and colonization.

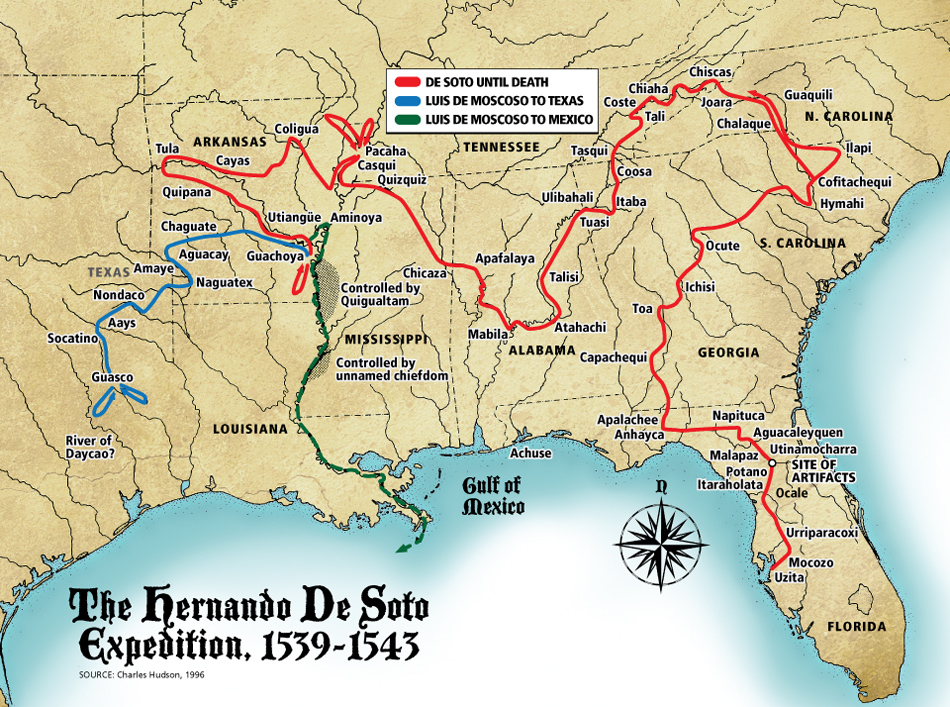

In 1539, explorer and conquistador Hernando de Soto led an expedition of 620 men and 220 horses deep into what is now Florida, Georgia, the Carolinas, Tennessee, Alabama and possibly Arkansas. He was fascinated by the stories of Cabeza de Vaca, one of the four survivors of the 1527-1536 Narváez expedition. With the help of Spaniard Juan Ortiz who was found living with the native Mocoso, de Soto recruited a series of local guides who were able to communicate with neighbouring tribes, thus acquiring local knowledge of the regions he crossed.

The expedition spent its first winter at Anhaica, capital of the Apalachee. The following year it journeyed northeast through Georgia, South Carolina (where de Soto was received by female chief Cofitachequi) and North Carolina (where the men spent a month searching for gold in the Appalachian Mountains), before turning west and south into Tennessee, Georgia and Alabama.

The following year the expedition headed west and reached the Mississippi River, where in May 1542, de Soto died of fever. His men continued on under the command of Luis de Moscoso Alvarado and reached Texas, before turning back and sailing down the Mississippi to the Gulf Coast.

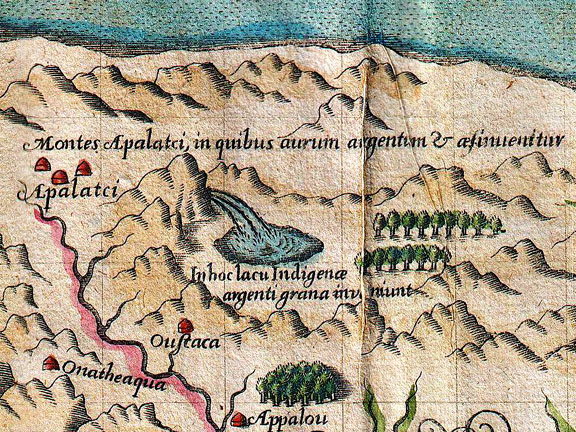

Though the De Soto expedition failed to find riches or establish a colony, it did contribute greatly to European knowledge of the geography, biology and ethnology of the land known as Florida. French artist and cartographer Jacques le Moyne de Morgues used it in his 1565 map of Florida, which was the first to use “Apalachee”, or the Latin “Apalatci”, to refer to the Appalachian Mountains.

Before long the entire southeast north of Florida – which itself spanned all of the southeast – became known as the land of Apalche, or Apalachee. The mountains to the north became known as the Allegheny Mountains, purportedly derived from the Lenape word for ‘fine river’.

In 1569, Flemish cartographer Gerardus Mercator completed a world map entitled Nova et Aucta Orbis Terrae Descriptio ad Usum Navigantium Emendate Accommodata, which was the first to show the Appalachian Mountains as a continuous mountain range stretching along the east coast of North America. It was also the first map to use the Mercator projection, whereby lines of constant compass bearing are straight lines on the map.

By the 19th century, both “Appalachian” and “Allegheny” were applied to the entire length of the eastern mountain system, replacing numerous more localized names such as Endless, Black and Smoky mountains. “Appalachian” became favored for the whole system following the publication of A.H. Guyot’s study On the Appalachian Mountain System in 1861, which is credited with securing scientific usage of “Appalachian”, and eventually leading to the popular endorsement of the term (Stewart, 1945).

In an ironic twist to the Appalachian story, the Conquistador Hernando de Soto was born in 1496 in Extremadura, Spain, near the country’s Appalachian mountain cousins … y El Sendero Internacional de los Apalaches!